Michelle Bachelet

| Michelle Bachelet | |

.jpg) |

|

|

34th President of Chile

|

|

| In office 11 March 2006 – 11 March 2010 |

|

| Preceded by | Ricardo Lagos |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Sebastián Piñera |

|

Minister of National Defense

|

|

| In office 7 January 2002 – 1 October 2004 |

|

| Preceded by | Mario Fernández |

| Succeeded by | Jaime Ravinet |

|

Minister of Health

|

|

| In office 11 March 2000 – 7 January 2002 |

|

| Preceded by | Álex Figueroa |

| Succeeded by | Osvaldo Artaza |

|

President pro tempore of the Union of South American Nations

|

|

| In office 23 May 2008 – 10 August 2009 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Rafael Correa |

|

|

|

| Born | 29 September 1951 Santiago, Chile |

| Political party | Socialist Party |

| Alma mater | University of Chile |

| Profession | Paediatric epidemiologist |

| Religion | Agnosticism |

| Signature | |

Verónica Michelle Bachelet Jeria (Spanish pronunciation: [miˈtʃel βatʃeˈlet]; born September 29, 1951) is a moderate socialist politician who was President of Chile from 11 March 2006 to 11 March 2010—the first woman president in the country's history. She won the 2006 presidential election in a runoff, beating center-right US dollar billionaire businessman and former senator Sebastián Piñera with 53.5% of the vote. She campaigned on a platform of continuing Chile's free-market policies, while increasing social benefits to help reduce the gap between rich and poor.]. She was inaugurated on March 11, 2006.

Bachelet, a pediatrician and epidemiologist with studies in military strategy, served as Health Minister and Defense Minister under President Ricardo Lagos. She is a separated mother of three and describes herself as an agnostic.[1] She speaks Spanish (her native language), English, German, Portuguese and French.[2] In 2009 Forbes magazine ranked her as the 22nd in the list of the 100 most powerful women in the world[3] (she was #25 in 2008[4], #27 in 2007,[5] and #17 in 2006).[6] In 2008, TIME magazine ranked her 15 on its list of the world's 100 most influential people.[7]

Contents |

Family background

Bachelet is the second child of archaeologist Ángela Jeria Gómez and Air Force Brigadier General Alberto Bachelet Martínez. Her paternal great-great-grandfather, Louis-Joseph Bachelet Lapierre, was a French wine merchant from Chassagne-Montrachet who emigrated to Chile with his Parisian wife, Françoise Jeanne Beault, in 1860 hired as a wine-making expert by the Subercaseaux vineyards in southern Santiago. Bachelet Lapierre's son, Germán—Michelle Bachelet's great-grandfather—was born in Santiago in 1862 and married in 1891 to Luisa Brandt Cadot, a Chilean of French-Swiss origin, giving birth in 1894 to Michelle Bachelet's grandfather Alberto Bachelet Brandt. Her maternal great-grandfather, Máximo Jeria Chacón, of Greek ancestry, was the first person to receive a degree in agronomic engineering in Chile and founded several agronomy schools in the country.[8] He married Lely Johnson, the daughter of an English physician working in the country. Their son, Máximo Jeria Johnson, married Angela Gómez Zamora, and gave birth to Michelle Bachelet's mother, Ángela Margarita in 1926.

Early life and career

Childhood years

Bachelet was born in Santiago, and spent many of her childhood years traveling around her native Chile, moving with her family from one military base to another. She lived and attended primary school in Quintero, Cerro Moreno, Antofagasta and San Bernardo. In 1962 she moved with her family to the United States, where her father was assigned to the military mission at the Chilean Embassy in Washington, DC, USA. Her family lived for almost two years in Bethesda, Maryland, where she attended Western Junior High School (now Westland Middle School) and learned to speak English fluently.[9] Returning to Chile in 1964, she graduated from high school in 1969 at Liceo Nº 1 Javiera Carrera, a prestigious girls' public school, finishing near the top of her class.[10][11] There she was president of her class, a member of the school's choir and volleyball teams, and part of a theater group and a music band called Las Clap Clap which she helped found, that toured around several school festivals. She entered medical school at the University of Chile in 1970, after obtaining one of the highest national scores in the university admission test.[10][11] She originally wanted to study sociology or economics, but was prevailed upon by her father to study medicine instead.[12] She has said she opted for medicine because it was "a concrete way of helping people cope with pain" and "a way to contribute to improve health in Chile."[2]

Torture and exile

Facing growing food shortages, the government of Salvador Allende placed Bachelet's father in charge of the Food Distribution Office. When General Augusto Pinochet came to power in the September 11, 1973 coup, General Bachelet, refusing exile, was detained at the Air War Academy under charges of treason. Following months of daily torture at Santiago's Public Prison, on March 12, 1974, he suffered a cardiac arrest that resulted in his death. On January 10, 1975, Bachelet and her mother were detained at their apartment by two DINA agents, who blindfolded them and drove them to Villa Grimaldi, a notorious secret detention center in Santiago, where they were separated and submitted to interrogation and torture.[13] Some days later they were transferred to Cuatro Álamos ("Four Poplars") detention center, where they were held until the end of January. Later in 1975, thanks to sympathetic connections in the military, both were exiled to Australia, where Bachelet's older brother Alberto had moved in 1969.[10]

In May 1975, Bachelet left Australia and moved to East Germany, to an apartment assigned to her by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) government in Am Stern, Potsdam; her mother joined her a month later, living separately in Leipzig. In October 1976 she began working at a communal clinic in the Babelsberg neighborhood, as a preparation step to continue her medical studies at an East German university. During this period she met architect Jorge Leopoldo Dávalos Cartes, another Chilean exile, whom she married in 1977. In January 1978 she went to Leipzig to learn German at the Karl Marx University's Herder Institute (now the University of Leipzig). Her first child with Dávalos, Jorge Alberto Sebastián, was born there in June 1978. She returned to Potsdam in September 1978 to continue her medical studies at the Humboldt University of Berlin for two years. Five months after enrolling as a student, however, she obtained authorization to return to her country.[14]

Return to Chile

In February 1979, Bachelet returned to Santiago, Chile from East Germany. Her medical school credits from the GDR were not transferred, forcing her to resume her studies from where she had left off before fleeing the country. She graduated as M.D. on January 7, 1983[15]. She wished to work in the public sector wherever attention was most needed, applying for a position as general practitioner; her petition was, however, rejected by the military government on "political grounds."[2] Instead, because of her academic performance and published papers, she earned a scholarship to specialize in pediatrics and public health at Roberto del Río Children's Hospital (1983–1986). During this time she also worked at PIDEE (Protection of Children Injured by States of Emergency Foundation), a non-governmental organization helping children of the tortured and missing in Santiago and Chillán. She was head of the foundation's Medical Department between 1986 and 1990. Some time after her second child with Dávalos, Francisca Valentina, was born in February 1984, she and her husband legally separated.

Between 1985 and 1987 Bachelet had a romantic relationship with Alex Vojkovic Trier,[16] an engineer and spokesman for the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front, an armed group which among other activities attempted to assassinate Augusto Pinochet in 1986. This affair turned into a minor issue during her presidential campaign, during which she argued that she never supported any of Vojkovic's activities.[8]

In 1990, after democracy was restored in Chile, Bachelet worked for the Ministry of Health's West Santiago Health Service and was a consultant for the Pan-American Health Organization, the World Health Organization and the German Corporation for Technical Cooperation. While working for the National AIDS Commission (Conasida) she became romantically involved with Aníbal Hernán Henríquez Marich, a fellow physician—and right-wing Pinochet supporter—who fathered her third child, Sofía Catalina, in December 1992; their relationship ended, however, a few years later. Between March 1994 and July 1997, Bachelet worked as Senior Assistant to the Deputy Health Minister.

Driven by an interest in civil-military relations, in 1996 Bachelet began studies in military strategy at the National Academy for Strategic and Policy Studies (Anepe) in Chile, obtaining first place in her class.[2] Her student achievement earned her a presidential scholarship, permitting her to continue her studies in the United States at the Inter-American Defense College in Washington, D.C., completing a Continental Defense Course in 1998. That same year she returned to Chile to work for the Defense Ministry as Senior Assistant to the Defense Minister. She subsequently graduated from a Master's program in military science at the Chilean Army's War Academy.

Political life

Involvement in politics

In her first year as a university student (1970), Bachelet became a member of the Socialist Youth (then presided by future deputy and later disappeared physician Carlos Lorca, who has been cited as her political mentor[17]), and was an active supporter of the Popular Unity. In the immediate aftermath of the coup, she and her mother worked as couriers for the underground Socialist Party directorate that was trying to organize a resistance movement; eventually almost all of them were captured and disappeared.[18] Following her return from exile she became politically active during the second half of the 1980s, fighting —though not on the front line—for the re-establishment of democracy in Chile. In 1995 she became part of the party's Central Committee, and from 1998 until 2000 she was an active member of the Political Commission.

In 1996 Bachelet ran against future presidential adversary Joaquín Lavín for the mayorship of Las Condes, a wealthy Santiago suburb and a right-wing stronghold. Lavín won the 22-candidate election with nearly 78% of the vote, while she finished fourth at 2.35%. At the 1999 presidential primary of Coalition of Parties for Democracy (CPD), Chile's governing coalition since 1990, she worked for Ricardo Lagos's nomination, heading the Santiago electoral zone.

Work as minister

On March 11, 2000 Bachelet—virtually unknown at the time—was appointed Minister of Health by President Ricardo Lagos. She began an in-depth study of the public health-care system that led to the AUGE plan a few years later. She was also given the task of eliminating waiting lists in the saturated public hospital system within the first 100 days of Lagos's government. She reduced waiting lists by 90%, but was unable to eliminate them completely[8] and offered her resignation, which was promptly rejected by the President. Controversially, she allowed free distribution of the morning-after pill for victims of sexual abuse.

On January 7, 2002 Bachelet was appointed Defense Minister, becoming the first woman to hold this post in a Latin American country and one of the few in the world. While Minister of Defense she promoted reconciliatory gestures between the military and victims of the dictatorship, culminating in the historic 2003 declaration by General Juan Emilio Cheyre, head of the army, that "never again" would the military subvert democracy in Chile. She also oversaw a reform of the military pension system and continued with the process of modernization of the Chilean armed forces with the purchasing of new military equipment, while engaging in international peace operations.

A moment which has been cited as key to Bachelet's chances to the presidency came during a flood in northern Santiago where she, as Defense Minister, led a rescue operation on top of an amphibious tank, wearing a cloak and military cap.[8][19][20]

Presidential candidacy

In late 2004, following a surge of her popularity in opinion polls, Bachelet was established as the only CPD figure able to defeat Lavín, and she was asked to become the Socialists' candidate for the presidency.[21] She was at first hesitant to accept the nomination as it was never one of her goals, but finally agreed because she felt she could not disappoint her supporters.[22] On October 1 of that year she was freed from her government post in order to begin her campaign and to help the CPD at the municipal elections. On January 28, 2005 she was named the Socialist Party's candidate for president.

An open primary scheduled for July 2005 to define the sole presidential candidate of the CPD was canceled after Bachelet's only rival, Christian Democrat Soledad Alvear, a cabinet member in the first three CPD administrations, pulled out early due to a lack of support within her own party and in opinion polls.

At the December 2005 election, Bachelet faced the center-right candidate Sebastián Piñera (RN), the right-wing candidate Joaquín Lavín (UDI) and the far-left candidate Tomás Hirsch (JPM). As predicted by opinion polls, she failed to obtain the absolute majority needed to win the election outright, winning 46% of the vote. In the runoff election on January 15, 2006, Bachelet faced Piñera, and won the presidency with 53.5% of the vote, thus becoming her country's first female elected president and the first woman who was not the wife of a previous head of state or political leader to reach the presidency of a Latin American nation in a direct election.

On January 30, 2006, after being declared President-elect by the Elections Qualifying Court (Tricel), Bachelet announced her cabinet of ministers, which was unprecedentedly composed of an equal number of men and women, as was promised during her campaign. In keeping with the coalition's internal balance of power she named seven ministers from the Christian Democrat Party (PDC), five from the Party for Democracy (PPD), four from the Socialist Party (PS), one from the Social Democrat Radical Party (PRSD) and three without party affiliation. In the days that followed, she named the group of deputy ministers and regional intendants, following the same rule of "gender parity."

Presidency

| The Bachelet Cabinet | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OFFICE | NAME | PARTY | TERM |

| President | Michelle Bachelet | PS | Mar. 11, 2006 – Mar. 11, 2010 |

| Interior | Andrés Zaldívar | DC | Mar. 11, 2006 – Jul. 14, 2006 |

| Belisario Velasco | DC | Jul. 14, 2006 – Jan. 4, 2008 | |

| Edmundo Pérez Yoma | DC | Jan. 8, 2008 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Foreign Affairs | Alejandro Foxley | DC | Mar. 11, 2006 – Mar. 13, 2009 |

| Mariano Fernández | DC | Mar. 13, 2009 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Defense | Vivianne Blanlot | PPD | Mar. 11, 2006 – Mar. 27, 2007 |

| José Goñi | PPD | Mar. 27, 2007 – Mar. 12, 2009 | |

| Francisco Vidal | PPD | Mar. 12, 2009 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Finance | Andrés Velasco | Ind. | Mar. 11, 2006 – Mar. 11, 2010 |

| Secy. Gen. of Presidency |

Paulina Veloso | PS | Mar. 11, 2006 – Mar. 27, 2007 |

| José Antonio Viera-Gallo | PS | Mar. 27, 2007 – Mar. 10, 2010 | |

| Secy. Gen. of Government |

Ricardo Lagos Weber | PPD | Mar. 11, 2006 – Dec. 6, 2007 |

| Francisco Vidal | PPD | Dec. 6, 2007 – Mar. 12, 2009 | |

| Carolina Tohá | PPD | Mar. 12, 2009 – Dec. 14, 2009 | |

| Pilar Armanet | PPD | Dec. 18, 2009 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Economy | Ingrid Antonijevic | PPD | Mar. 11, 2006 – Jul. 14, 2006 |

| Alejandro Ferreiro | DC | Jul. 14, 2006 – Jan. 8, 2008 | |

| Hugo Lavados | DC | Jan. 8, 2008 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Planning | Clarisa Hardy | PS | Mar. 11, 2006 – Jan. 8, 2008 |

| Paula Quintana | PS | Jan. 8, 2008 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Education | Martín Zilic Hrepic | DC | Mar. 11, 2006 – Jul. 14, 2006 |

| Yasna Provoste (impeached) | DC | Jul. 14, 2006 – Apr. 3, 2008 | |

| René Cortázar (interim) | DC | Apr. 3, 2008 – Apr. 18, 2008 | |

| Mónica Jiménez | DC | Apr. 18, 2008 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Justice | Isidro Solís | PRSD | Mar. 11, 2006 – Mar. 27, 2007 |

| Carlos Maldonado | PRSD | Mar. 27, 2007 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Labor | Osvaldo Andrade | PS | Mar. 11, 2006 – Dec. 10, 2008 |

| Claudia Serrano | PS | Dec. 15, 2008 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Public Works | Eduardo Bitrán | PPD | Mar. 11, 2006 – Jan. 11, 2008 |

| Sergio Bitar | PPD | Jan. 11, 2008 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Health | María Soledad Barría | PS | Mar. 11, 2006 – Oct. 28, 2008 |

| Álvaro Erazo | PS | Nov. 6, 2008 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Housing & Urbanism |

Patricia Poblete | DC | Mar. 11, 2006 – Mar. 11, 2010 |

| Agriculture | Álvaro Rojas | DC | Mar. 11, 2006 – Jan. 8, 2008 |

| Marigen Hornkohl | DC | Jan. 8, 2008 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Mining | Karen Poniachik | Ind. | Mar. 11, 2006 – Jan. 8, 2008 |

| Santiago González | PRSD | Jan. 8, 2008 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Transport & Telecom |

Sergio Espejo | DC | Mar. 11, 2006 – Mar. 27, 2007 |

| René Cortázar | DC | Mar. 27, 2007 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| National Assets | Romy Schmidt | PPD | Mar. 11, 2006 – Jan. 6, 2010 |

| Jacqueline Weinstein | PPD | Jan. 6, 2010 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Energy | Karen Poniachik | Ind. | Mar. 11, 2006 – Mar. 29, 2007 |

| Marcelo Tokman | PPD | Mar. 29, 2007 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Women | Laura Albornoz | DC | Mar. 11, 2006 – Oct. 20, 2009 |

| Carmen Andrade | PS | Oct. 20, 2009 – Mar. 11, 2010 | |

| Culture & the Arts |

Paulina Urrutia | Ind. | Mar. 11, 2006 – Mar. 11, 2010 |

| Environment | Ana Lya Uriarte | PS | Mar. 27, 2007 – Mar. 11, 2010 |

Bachelet was sworn in as President of the Republic of Chile on March 11, 2006 in a ceremony held in a plenary session of the National Congress in Valparaíso which was attended by a record number of foreign heads of states and delegates.

Domestic affairs

Most of Bachelet's first three months as president were spent working on 36 measures she had promised during her campaign to implement during her first 100 days in office. They ranged from simple presidential decrees, such as providing free health care for older patients, to complex bills to reform the social security system and the electoral system.

Bachelet's first political crisis came in late April 2006, when massive high school student demonstrations—unseen in three decades—broke out throughout the country, demanding a rise of quality levels in public education. These protests, and a sharp drop in her popularity, forced Bachelet to reshuffle her cabinet after only four months in office—a record in the country's history.[23]

The final months of 2006 were marred by reports of alleged misspending of public funds during the previous administration, specially in Chiledeportes, a government sports funding organization. There were also accusations of misappropriation of funds channeled through phantom firms, and identity theft to fund congressional campaigns in late 2005. The scandal prompted Bachelet to present an anti-corruption plan in late November. Other issues faced by Bachelet during her first year included the death of general Augusto Pinochet, and a controversial decree allowing for the free distribution of the "morning-after pill" to women older than 14 years of age without parental consent[24], a nine-month Government-Congress deadlock over the naming of a new Controller General, and a difficult implementation of a new public transport system for the capital Santiago. This last issue escalated into a major crisis that damaged her popularity and which resulted in a second cabinet adjustment two weeks into her second year.

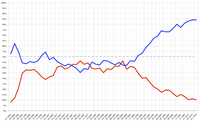

Bachelet's popularity dipped in her second year, reaching a low of 35% approval, 46% disapproval in September, 2007. This fall was mainly attributed to the fiasco of the Transantiago transport system, put into motion in February that year. On her decision not to abort the plan's start, she said in April 2007 she was given erroneous information which caused her to act against her "instincts."[25] That same month she had a disastrous public relations incident when a group of earthquake victims she was visiting in the southern region of Aisén received her bearing black flags and berated her publicly on television, accusing her of arriving late and asking her to leave. In November, following months of discussions, Bachelet reached preliminary agreements with the opposition on the issues of education reform and measures to tackle urban crime. On the economic side, while the year saw the lowest unemployment rates since 1998, and growth was forecast to be above 5% (better than 2006's disappointing 4%), inflation was nearly twice the Central Bank's upper target of 4%—due to a rise in food prices, the result of a harsh winter that cut harvests—and the peso strengthened to an eight-year high against the US dollar, hurting exporters.

Bachelet began her term with an unprecedented absolute majority in both chambers of Congress—before appointed senators were eliminated in the 2005 constitutional reforms the CPD never had a majority in the Senate—but she was soon faced with internal opposition coming from a number of dissatisfied lawmakers from both chambers of Congress, the so-called díscolos ("disobedient," "ungovernable"), which jeopardized the coalition's narrow—and historic—Congress majority on a number of key government-sponsored bills during much of her first half in office, and forced her to negotiate with a right-wing opposition she saw as being obstructionist[26][27]. During the course of 2007 the government lost its absolute majority in both chambers of Congress, as several senators and deputies from the CPD became independent.

According to The Economist magazine the government of Bachelet opted to make social protection and the promotion of equality of opportunity her main priority. Since becoming President, her government built 3,500 crèches daycare for poorer children. It introduced a universal minimum state pension and extended free health care to cover many serious conditions[28]. A new housing policy aimed at abolishing the last remaining shanty-towns in Chile by 2010 featured grants to the poorest families. Some of them had to pay just US$400 for a house costing about US$20,000.[29].

In October 2009 Ms Bachelet's popularity peaked at 80 percent according to a public opinion poll by conservative polling institute Adimark GfK.[30], and in March 2010 she showed an approval rating of 84%, and in terms of specific characteristics attributed to Chile's president, 'loved by Chileans' reached a record 96%[31].

The Chilean Constitution does not allow a president to serve two consecutive terms, so Bachelet left office in March 2010; she was succeeded as president by her 2006 opponent Sebastián Piñera.

Bachelet has not ruled out a return to the presidency at the next elections in 2014[32].

Foreign relations

During her first year in office Bachelet faced continuing problems from neighbors Argentina and Peru. On July 2006 she sent a letter of protest to Argentine president Néstor Kirchner after his government issued a decree increasing export tariffs of natural gas to Chile, which was considered by Bachelet to be a violation of a tacit bilateral agreement. A month later a long-standing border dispute resurfaced after Argentina published some tourist maps showing contested territory in the south—the Southern Patagonian Ice Field (Campo de Hielo Patagónico Sur)—as Argentine, violating an agreement not to define a border over the area. In early 2007 Peru accused Chile of unilaterally redefining their shared sea boundary in a law, passed by Congress, which detailed the borders of the new administrative region of Arica and Parinacota. The impasse was resolved by the Chilean Constitutional Tribunal, which declared the particular section of the law unconstitutional. In March 2007, the Chilean state-owned—but editorially independent—television channel TVN cancelled the broadcast of a documentary about the War of the Pacific after a cautionary call was made to the stations' board of directors by Chilean Foreign Relations Minister Alejandro Foxley, apparently acting on demands made by the Peruvian ambassador to Chile; the show was finally broadcast in late May of that year. In August 2007 the Chilean government filed a formal diplomatic protest to Peru and summoned home its ambassador, after Peru published an official map claiming a part of the Pacific Ocean that Chile considers its sovereign territory. Peru said this was just another step in its plans to bring the dispute to the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

Chile's October 16, 2006 vote in the United Nations Security Council election—with Venezuela and Guatemala deadlocked in a bid for the two-year, non-permanent Latin American and Caribbean seat on the Security Council—developed into a major ideological issue in the country and was seen as a test for Bachelet. The governing coalition was divided between the Socialists, who supported a vote for Venezuela, and the Christian Democrats, who strongly opposed it. The day before the vote the president announced (through her spokesman) that Chile would abstain, citing as reason a lack of regional consensus over a single candidate, ending months of speculation. On March 2007 Chile's ambassador to Venezuela, Claudio Huepe, revealed in an interview with teleSUR that Bachelet personally told him that she initially wanted to vote for Venezuela, but then "there were a series of circumstances that forced me to abstain."[33] The government quickly recalled Huepe and accepted his resignation.

Continuing the coalition's free-trade strategy, in August 2006 Bachelet promulgated a free trade agreement with the People's Republic of China (signed under the previous administration of Ricardo Lagos), the first Chinese free-trade agreement with a Latin American nation; similar deals with Japan and India were promulgated in August 2007. In October 2006, Bachelet promulgated a multilateral trade deal with New Zealand, Singapore and Brunei, the Trans-Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership (P4), also signed under Lagos' presidency. She also held free-trade talks with other countries, including Australia, Vietnam, Turkey and Malaysia. Regionally, she signed bilateral free trade agreements with Panama, Peru and Colombia.

At the beginning of 2010 Chile became the OECD’s 31st member, and its first in South America. This acceptance for OECD membership marked international recognition of nearly two decades of democratic reform and sound economic policies; for the OECD, Chile’s membership was a major milestone in its mission to build a stronger, cleaner and fairer global economy[34].

Notes and references

- ↑ Correa, Raquel (April 3, 2005). "Title unknown" (in Spanish). El Mercurio. http://www.mujeresconbachelet.cl/Pages/EntrevistasCorrea.html. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Biografía Michelle Bachelet" (in Spanish). Gobierno de Chile. http://www.gobiernodechile.cl/viewPresidenta.aspx?Idarticulo=22478. Retrieved 2007-02-02.

- ↑ "The 100 Most Powerful Women: #22 Michelle Bachelet". Forbes. August 19, 2009. http://www.forbes.com/lists/2009/11/power-women-09_Michelle-Bachelet_Z2QJ.html. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ↑ "The 100 Most Powerful Women: #25 Michelle Bachelet". Forbes. August 27, 2008. http://www.forbes.com/lists/2008/11/biz_powerwomen08_Michelle-Bachelet_Z2QJ.html. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ "The 100 Most Powerful Women: #27 Michelle Bachelet". Forbes. August 31, 2007. http://www.forbes.com/lists/2007/11/biz-07women_Michelle-Bachelet_Z2QJ.html. Retrieved 2007-08-31.

- ↑ "The 100 Most Powerful Women: #17 Michelle Bachelet". Forbes. August 31, 2006. http://www.forbes.com/lists/2006/11/06women_Michelle-Bachelet_Z2QJ.html. Retrieved 2006-08-31.

- ↑ "The World's Most Influential People - The 2008 TIME 100 - Leaders & Revolutionaries - Michelle Bachelet". TIME. May 1, 2008. http://www.time.com/time/specials/2007/article/0,28804,1733748_1733757_1735593,00.html. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Biografías de Líderes Políticos CIDOB: Michelle Bachelet Jeria" (in Spanish). Fundació CIDOB. March 9, 2007. http://www.cidob.org/es/documentacion/biografias_lideres_politicos/america_del_sur/chile/michelle_bachelet_jeria. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- ↑ Rohter, Larry (January 16, 2006). "Woman in the News; A Leader Making Peace With Chile's Past". The New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10C10FA3F5B0C758DDDA80894DE404482. Retrieved 2006-01-16.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "La vida de la primera Presidenta de Chile" (in Spanish). La Nación. January 16, 2006. http://www.lanacion.cl/prontus_noticias/site/artic/20060116/pags/20060116011432.html. Retrieved 2006-01-16.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Los años de Alvear y Bachelet en el Liceo 1" (in Spanish). La Tercera. October 10, 2004. http://www.latercera.cl/medio/articulo/0,0,3255_5714_93568820,00.html. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ↑ "Biografía de Michelle Bachelet" (in Spanish). La Nación. http://www.lanacion.cl/prontus_noticias/site/artic/20060115/pags/20060115211311.html. Retrieved 2006-01-15.

- ↑ Davison, Phil (December 12, 2005). "Single mother poised to be Chilean President". The Independent (London). http://news.independent.co.uk/world/americas/article332446.ece. Retrieved 2005-12-12.

- ↑ "Las huellas de Bachelet en Alemania Oriental" (in Spanish). La Tercera. April 9, 2006. http://www.tercera.com/medio/articulo/0,0,3255_66602343_199370524,00.html. Retrieved 2006-04-09.

- ↑ Registro Nacional de Prestadores Individuales de Salud, Superintendencia de Salud.

- ↑ "La historia del ex frentista que fue pareja de Bachelet" (in Spanish). La Tercera. July 10, 2005. http://www.latercera.cl/medio/articulo/imprimir/0,0,3255_66602343_147819372,00.html. Retrieved 2005-07-10.

- ↑ "El libro que emocionó a Bachelet" (in Spanish). Qué Pasa. http://www.latercera.cl/medio/articulo/0,0,38039290_101111578_310776715,00.html. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- ↑ "Las historias clandestinas de Bachelet" (in Spanish). La Tercera. December 9, 2007. http://papeldigital.info/ltrep/. Retrieved 2007-12-27.

- ↑ See image here.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Franklin, Jonathan (November 22, 2005). "'All I want in life is to walk along the beach, holding my lover's hand'". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/chile/story/0,13755,1648008,00.html. Retrieved 2005-11-22.

- ↑ Santa María, Orietta (January 19, 2006). "'Estuve una semana encerrada en un cajón, vendada, atada'" (in Spanish). Las Últimas Noticias. http://www.lun.com/modulos/catalogo/paginas/2006/01/19/LUCST09LU1901.htm. Retrieved 2006-01-19.

- ↑ Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle reshuffled his cabinet in his sixth month as President, with a six-year mandate, two more than Bachelet.

- ↑ "Bachelet ya firmó decreto que autoriza entrega de la 'píldora'" (in Spanish). Radio Cooperativa. January 29, 2007. http://www.cooperativa.cl/p4_noticias/antialone.html?page=http://www.cooperativa.cl/p4_noticias/site/artic/20070129/pags/20070129214009.html. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ↑ "Belisario Velasco afirma que Bachelet también conoció informe del Metro que advertía colapso del Transantiago" (in Spanish). La Tercera. July 30, 2007. http://www.latercera.cl/medio/articulo/0,0,3255_5664_285592518,00.html. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ↑ "La Moneda fustigó el "obstruccionismo" de la derecha en 2006" (in Spanish). Radio Cooperativa. December 26, 2006. http://www.cooperativa.cl/p4_noticias/site/artic/20061226/pags/20061226143055.html. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ "Gobierno quiere debate “pausado y sin presiones”" (in Spanish). La Nación. November 22, 2007. http://lanacion2007.altavoz.net/prontus_noticias_v2/site/artic/20071121/pags/20071121215812.html. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ "Chile's surprising president: The Bachelet model" (in Spanish). The Economist. September 17, 2009. http://www.economist.com/world/americas/displaystory.cfm?story_id=14460079. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ↑ "The strange chill in Chile" (in Spanish). The Economist. September 17, 2009. http://www.economist.com/world/americas/displaystory.cfm?story_id=14456913. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ↑ http://www.nasdaq.com/aspx/stock-market-news-story.aspx?storyid=200912021216dowjonesdjonline000556&title=chile-president-bachelets-approval-drops-to-77in-novpoll

- ↑ http://www.nasdaq.com/aspx/stock-market-news-story.aspx?storyid=201003090924dowjonesdjonline000277&title=chile-president-bachelet-maintains-84-approval-after-earthquake--poll

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VW9kEcgXW20

- ↑ "Chilevisión Noticias Última Mirada". Chilevisión. March 13, 2007. http://www.chilevision.cl/. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ↑ "Chile signs up as first OECD member in South America". OECD. January 11, 2010. http://www.oecd.org/document/1/0,3343,en_2649_34487_44365210_1_1_1_1,00.html. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

External links

- (Spanish) Presidencia de la República official site (English version)

- (Spanish) Official presidential campaign site

- (Spanish) Biography by CIDOB Foundation

- PBS Newshour - Interview transcript with video

- "The woman taking Chile's top job" (BBC News)

- "The unexpected travails of the woman who would be president" (The Economist - December 8, 2005)

- "Bachelet's citizens' democracy" (The Economist - March 10, 2006)

- "With a New Leader, Chile Seems to Shuck Its Strait Laces" (The New York Times - March 8, 2006)

- "Welcome Madam Chilean President to Washington" —Council on Hemispheric Affairs

- Feature on Michelle Bachelet, with video, by the International Museum of Women.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Alex Figueroa |

Minister of Health 2000–2002 |

Succeeded by Osvaldo Artaza |

| Preceded by Mario Fernández |

Minister of National Defense 2002–2004 |

Succeeded by Jaime Ravinet |

| Preceded by Ricardo Lagos |

President of Chile 2006–2010 |

Succeeded by Sebastián Piñera |

|

|||||||